The “Cloud”, for all the marketing lingo and buzzwords flying around about it, is actually quite simple. At it’s core, the Cloud is simply computers connected across diverse areas and networks. That’s it. There’s no incantations or magic spells holding our digital age together – though on second thought, the engineers that design and keep these technologies working might as well be wizards. It can be hard to tell sometimes.

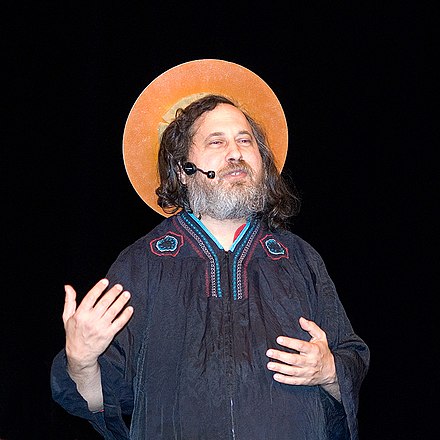

Speaking of wizards, meet Richard Stallman—founder of the GNU Project and a key figure in shaping today’s technology ecosystem. With his flowing beard and occasionally iconic attire, I could see how one might expect him to pull out a staff and cast a spell at any moment.

The Cloud, or what in my age we called the internet, has a heart that beats with the pulse of protocols like BGP – languages that routers speak to communicate with each other. With BGP, routers exchange info with each other to coordinate what internet destinations they’re able to reach. This magic allows your internet traffic to jump on the internet in Centreville, AL and get all the way to a server in San Francisco, CA efficiently and redundantly. All of this happens quickly and silently in the background when you’re scrolling TikTok or watching excellent videos about dishwashers on YouTube.

Part of what makes this system work are common locations where routers – those owned from ISPs and content providers alike – connect with each other, and trade internet traffic. It looks a bit like this:

Customer <-> ISP (AT&T, CSpire, etc.) <-> Internet Exchange <-> Netflix

In this example, the customer internet traffic exits their home, passes across their ISP’s network to an internet exchange. Netflix, connected to this hypothetical internet exchange, will then pass the video stream the customer requested back to the customer’s ISP at said exchange, which will journey back across the origin network and in to their streaming device of choice.

The more internet exchanges exist, and the closer they are to the users that utilize the services connected to them, the better and faster the overall internet feels for end users. If I live in Birmingham, Alabama and my local ISP is connected to a local internet exchange in my state where content providers are connected also in a central location like Montgomery – that content loads faster and snappier for me. Why? Because my traffic didn’t have to travel to a major internet hub like Dallas or Ashburn to reach me. Just like driving or flying, the more direct the route, the faster the trip.

Enter The MGMix

Alabama is blessed to have an internet exchange in this state. The City of Montgomery operates one called the MGMix out of the RSA Dexter Avenue Datacenter across the street from the State Capital Building in Montgomery. The MGMix boasts members that are well-connected such as Meta (Facebook) and Hurricane Electric.

I’ve been working with the City of Montgomery and the MGMix to get my ISP, Alabama Lightwave, connected to this internet exchange and have been quite successful so far bringing these direct connections to my customers. So far, we’ve been able to establish peering with:

- Meta (Facebook)

- Hurricane Electric

- JMF Solutions

- Whitesky Communications

- Pine Belt Communications

- Packet Clearing House

- Internet Systems Consortium

- City of Montgomery

In addition to the speed advantages this brings to my internet users at Alabama Lightwave, the overall resiliency of the internet also improves when networks can connect to each other in more locations. Let’s suppose that a data center in Nashville sustained a significant connectivity disruption. Assuming a failure there, Alabama is impacted badly. However, if networks in Alabama are able to communicate in Montgomery without first having to connect with one another out-of-state or worse out-of-region, the overall economy and government becomes most robust as a result, and less prone to failure when regional hubs go offline as has happened before. Ensuring minimal disruption is crucial, especially during regional disasters.

Another key benefit of ix presence is “data sovereignty”. In a world where throttling and censorship becomes ever-more-concerning, if network operators can talk directly with BGP and exchange traffic at ix locations without going through Wall St. telecommunications companies, they can help ensure free-flowing data regardless of the political orientations of middle-man network operators or interference from nefarious actors.

It’s crucial for Alabama network operators to invest in strengthening the MGMix, AUBix, and other regional IXs. The more we build neutral, local interconnection points, the more we move toward a decentralized, resilient internet. And a faster internet too!

Leave a Reply